English is an unruly language, its spelling, grammar and vocabulary unsupervised for most of its history. There have been many attempts, however, to bring a degree of order and simplicity to the language.

English is an unruly language, its spelling, grammar and vocabulary unsupervised for most of its history. There have been many attempts, however, to bring a degree of order and simplicity to the language.

Spelling

One of the first steps was to standardise spelling. Before dictionaries were printed in the 17th century, writers took an individual approach to word construction. Even Shakespeare, the English language’s greatest wordsmith, spelled his name six different ways. The dictionaries also reflected a growing desire to spread the use of English as a medium for serious literature. Most books in England before the 16th century were written in Latin, including even early textbooks on English grammar, as were most government and legal documents.

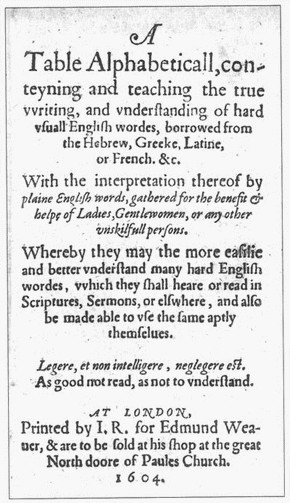

The first book on English spelling was published in 1582, and the first dictionary in 1604. Even then, the habit of loose spelling was on display, as in some versions the dictionary’s author spelled the word ‘words’ in two different ways on the cover page. Until the 20th century, the most influential dictionary was Samuel Johnson’s, published in 1755. It was a work of astounding scholarship and was supposed to be a record of the whole language, which took him 11 years to write. It became the reference for ‘correct’ usage and spelling. Yet even today, with hundreds of dictionaries available, there is still considerable disagreement on spelling. By some estimates, six percent of English words are not agreed upon. These include accessary/accessory; all right/alright; ageing/aging.

Grammar

Serious attempts to standardise grammar came later. In the first-half of the 19th century, some 900 grammar books were published, bringing a tear to the eye of most English students. Interestingly, the most comprehensive study of English grammar occurred in non-English speaking countries. For example, Jacob Grimm, of the famous Grimm Brothers, included an extensive analysis of English grammar in his book Deutsche Grammatik, published in 1857.

Arguably, the most influential book on English grammar is Fowler’s A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926). Dense and comprehensive, it is also known for its humorous passages. On split infinitives (to boldly go or to go boldly), it states: The English-speaking world may be divided into (1) those who neither know nor care what a split infinitive is; (2) those who do not know, but care very much; (3) those who know and condemn; (4) those who know and approve; and (5) those who know and distinguish. . . . Those who neither know nor care are the vast majority, and are a happy folk, to be envied by the minority classes.

A New Lingua Franca

In the 20th century, English became the world’s lingua franca in many spheres of life including business, politics, communication, technology and transport. It increasingly meant non-native speakers needed to communicate with each other in English. Only the most dedicated learners of English would be bothered to open Fowler’s book on grammar (or any book on grammar) so there was a perceived need to simplify the language to facilitate communication. These new forms of English are called controlled English.

Basic & Special English

One of the earliest examples is Basic English, developed in the 1930s to assist teaching English as a second language. It uses 850 words and only 18 of them are verbs. The assumption was that noun use in English is very easy, but verb use and conjugation are not. Consequently, grammar in Basic English is considerably constrained, for example, by using only active sentences. Basic English was the basis for Special English, developed by the radio station Voice of America (VOA), which broadcasts mainly to non-native English speakers. Special English uses only 1510 words (as opposed to the 25,000 odd words a native speaker knows on average), and does not use idioms, collocations or phrasal verbs, though the grammar is not as restricted as in Basic English.

“Say again?”

One of the most common forms of controlled English is SeaSpeak. Adopted in 1988 by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), it is for use in ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore communications using a group of standardized English phrases for navigational and emergency communications. SeaSpeak is as concise and unambiguous as possible. Message markers at the beginning of the communication indicate the nature of what follows, such as advice, information, instruction, intention, question, request, warning, or a response to one of these. For example, if a ship captain using a radio requires some information from a nearby port, he starts with “Question” followed by the message. If a message is not heard properly, rather than the reply being “I can’t hear you” or “What did you say?”, the radio operator should only say “Say again”. Similarly, AirSpeak is used for civil aviation. It also uses restricted grammar and words to avoid ambiguity, and international agreements ensure that all pilots are trained in this English.

Keeping it Simple

Another common type of controlled English is Simplified Technical English (STE), which is used in technical manuals. The language is simplified specifically to avoid translations, and is designed to be learnt quickly by non-English speakers. There are certain rules that must be adhered to, such as restricting noun clusters to 3, no -ing forms of verbs, and sentences should be a maximum of 20 words. It is, however, in the small vocabulary and concise language that its advantage is immediately discernible as a universal standard for users with a minimum knowledge of English. For example, a sentence not using STE would be written as:

THE SYNTHETIC LUBRICATING OIL USED IN THIS ENGINE CONTAINS ADDITIVES WHICH, IF ALLOWED TO COME INTO CONTACT WITH THE SKIN FOR PROLONGED PERIODS, CAN BE TOXIC THROUGH ABSORPTION.

Using STE, it becomes:

DO NOT GET THE ENGINE OIL ON YOUR SKIN. THE OIL IS POISONOUS. IT CAN GO THROUGH YOUR SKIN AND INTO YOUR BODY.

In addition to STE, there is Caterpillar Technical English (CTE). Designed by the company Caterpillar, this controlled language was developed to save on the translation costs of converting 20,000 user manuals into 50 languages.

Not Lost in Translation

In contrast, other forms of controlled English are specifically designed to be translated, and rely on a logical framework with input from different sectors of society, including business and computer language specialists. Simply put, the English can be read easily by anyone, but the grammar and vocabulary are actually formed using mathematical logic built up over time that computers, using specific software, can translate into any other language. One of the most common is Attempto Controlled English, developed by the University of Zurich.

Simple, Not Simplicity

Probably the most important and widespread attempt to simplify English is the Plain English Campaign. It began in England by a woman who was annoyed with unintelligible government forms. She took hundreds of the offending documents to the Parliament, and shredded the lot in a public display of disgust. The movement has had a huge influence in the simplification of government and legal documents in English-speaking countries. The US government, for example, passed the Plain Writing Act of 2010, requiring agencies to write in plain language. Writers are urged to avoid pretentious language or jargon, choose Anglo-Saxon words over Latin or Greek derived words, and never use clichés. It is not a dull way of reading or speaking English, but rather uses the simplest and most straightforward way of expressing an idea.

English will never be truly tamed. Nor should it be. Attempts to simplify the language and grammar merely reflects the international role of the language, and a versatility thrust upon it by creative minds who wanted to ease communications between people.

Sources:

A Table Alphabeticall by Robert Cawdrey (1604).

http://www.tcworld.info/rss/article/a-close-look-at-simplified-technical-english/

TOM McARTHUR. "SEASPEAK." Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language. 1998. Retrieved November 10, 2015 from Encyclopedia.com: http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O29-SEASPEAK.html

Linn, Andrew (2006), "English grammar writing", in Aarts, Bas; McMahon, April, Handbook of English Linguistics, Wiley-Blackwell. Pp. 824, pp. 78-79.

http://ogden.basic-english.org/

http://misunderstoodmariner.blogspot.ch/2011/10/seaspeak.html

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O29-AIRSPEAK.html

http://www.tcworld.info/rss/article/a-close-look-at-simplified-technical-english/

http://attempto.ifi.uzh.ch/site/

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.44.6405&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://www.plainlanguage.gov/whatisPL/

http://www.plainenglish.co.uk/

http://www.simplifiedenglish.net/What-Is-Controlled-Language-Simplified-Technical-English

Image: A Table Alphabeticall by Robert Cawdrey (1604), commonly recognised as the first English dictionary.

An interesting stroll through the history of how English has developed. What about the future? What thoughts are there on how it's going to continue to develop? Will there be continuing standardisation and simplification of the language on an international level?

I think the answer to those questions will depend on who "owns" English in the future. We may see a movement away from a perceived standard "proper" English, towards more regional variations, that I think will include a simplified approach to English grammar. We can see this due to the fact that more and more English conversations are between second-language speakers (ESL), and each person's language adapts (read simplifies) their language to this situation. For example, it has been noted that many ESL speakers when communicating with each other tend to not use phrasal verbs, even if they know them. Also, in the near future (if not already) a majority of English teachers are not mother-tongue speakers, meaning that regional variations come into the fold and multiply. Simplification may increase, but not standardisation.