Having just recently entered the seventh post-crisis year in the US, it is worth spending a few minutes to try to understand where we are now.

Having just recently entered the seventh post-crisis year in the US, it is worth spending a few minutes to try to understand where we are now.

We have been told by numerous experts that the US economy had finally reached its “escape velocity” last year, referring to the need for an economy to grow at a sufficiently fast rate to escape a recession and return to a normal long run rate of economic growth. The FED was also supposedly preparing its first try at rate normalization for the first time since 2006.

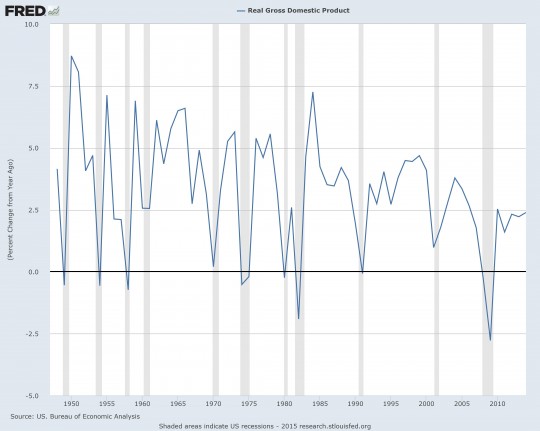

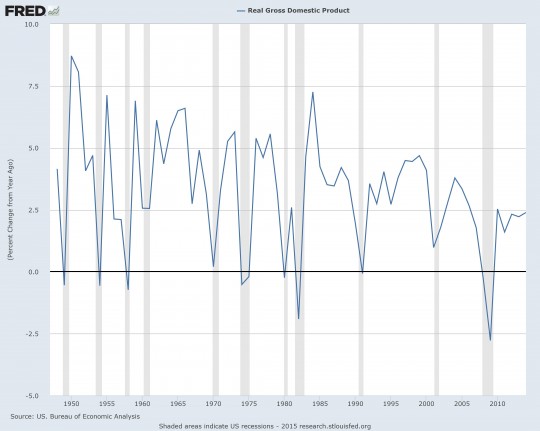

US GDP growth and unemployment measures registered a quite satisfactory performance over the past six years, at least relative to other countries. However, we should keep in mind that despite unprecedented fiscal and monetary easing, this is still the weakest post-recession recovery ever in the US.

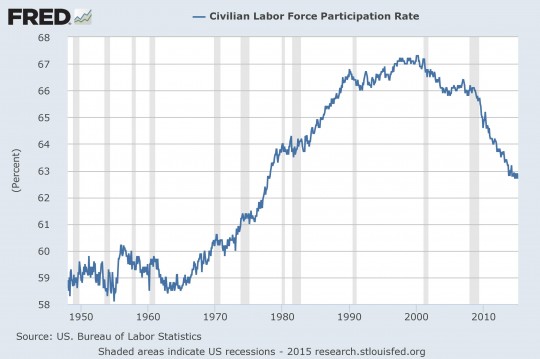

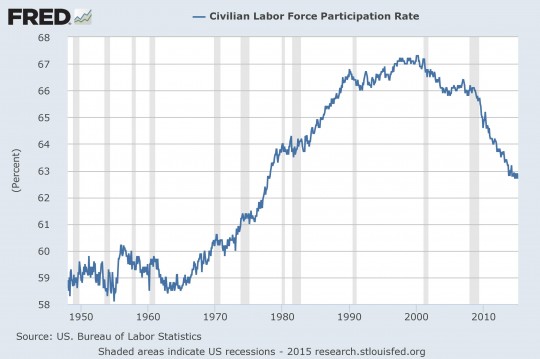

Not only that, but workforce participation rate, which is probably a more accurate way of measuring the underlying economics strengths, never recovered from the “great recession” and actually continued to collapse, reaching in March 2015 a level not seen since the mid-70’s. Given that the Baby Boom generation started retiring around 2010 and will continue through 2020, this trend will probably not reverse anytime soon.

In this context, with stock markets reaching new high after new high and all eyes pointed to next round of Quantitative Easing (QE), whatever comes next from the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan or the People’s Bank of China, it is maybe worth questioning the long term effects of such QE. Of course, stocks and credit markets benefited the most from this “largesse” of our central planners, but there are side and hidden effects that are not fully understood.

As Robert Merton, recipient of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, and Distinguished Professor of Finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management, recently pointed out:

“So, while QE has increased absolute wealth, it has simultaneously lowered relative wealth for a large class of investors. This could lead to the opposite of the desired effect for this group of investors. Lower relative wealth means investors need to save more to improve their funded status, especially where regulations are strict (i.e., divert funds from the business to the corporate pension fund or raise contributions for DC investors), and it results in less consumption and investment, and may not remove the deflationary overhang. Alternatively, investors could try to earn a higher return to improve their funded position. However, from 2003 to 2007 — before the financial crisis — funded status declined for most U.S. funds due to declining long rates, and the data shows it possibly led to an increased allocation to risky assets, which ended very badly in 2008. Depending on the size of absolute and relative investors, the central banks' moves may have no impact or may unintentionally lead to less consumption and investment. An alternate, more sophisticated approach to explaining why QE may not work to stimulate aggregate consumption is, perhaps, because the demographic mix of the U.S. (and most parts of the developed world) has shifted toward older people.”

That is not to say that Robert Merton is right and central banks are wrong, but even in the academic world, there is no widespread acceptance about QE’s benefits for societies as whole. In this case, Merton stresses the change in demographics in the western world as the main reason for the weak economic performance, despite an aggressive monetary policy stance.

As an aside, most of the stimulus plans adopted by various governments and central banks around the world in the aftermath of the Great Recession were labelled as “Keynesian”, giving them a quite strong intellectual and academic cover. But is it logical to think that John Maynard Keynes would have prescribed the same “medicine” today to a total different “body” than 70 years ago?

Perhaps the lesson to learn here is: be careful of what you wish for.

Author’s note: the title of this brief is a suggestion that central banks are perhaps creating a new financial bubble. The song was first presented by Mina at the San Remo festival in 1961. As it happens, when she is in love, she sees a thousand blue bubbles. In the author’s mind, any time a central banker speaks, markets falls in love with them.

Source : http://www.pionline.com/article/20150416/ONLINE/150419916/monetary-policy-its-all-relative

Photo credit: Nevit Dilmen (Own work) , via Wikimedia Commons

Having just recently entered the seventh post-crisis year in the US, it is worth spending a few minutes to try to understand where we are now.

Having just recently entered the seventh post-crisis year in the US, it is worth spending a few minutes to try to understand where we are now.

Dans le cadre de la crise grecque, la BCE pourrait également utiliser le Quantitative Easing, non ? Qu'en pensez-vous ?

Bonjour Laurent. La BCE a effectivement débuté son QE en mars 2015 mais la dette Grecque n'a pas été retenue "éligible" pour l'heure en tout cas.

http://www.bilan.ch/economie/bce-optimiste-rachats-dactifs-reste-ferme-face-grece

Ce n'est bien sûr que mon opinion, mais les QE ne sont en réalité qu'un moyen de prolonger artificiellement l'illusion de prospérité d'un occident vieillissant et surendetté.