Wines from the Champagne region of France date back to the Romans and enjoyed a close association with the French monarchy and nobility ever since Clovis' reign in the fifth century. He not only founded the kingdom of France, but also established Champagne as the traditional wine for royal coronations.

When Champagne became effervescent in the late 1700s, it was an instant success at the royal court and among the wealthy and titled. Champagne came to symbolise the spirit of France in the minds of many people, and its reputation continued to spread throughout the 19th century.

Nowadays no high society event in the world is complete without Champagne. Here we look at how Champagne is made to give you a greater appreciation of this world-renowned wine.

In France's Champagne region, the climate, soils, and aspect (terrain) determine the choice of plantings.

Pinot Noir accounts for 38 percent of Champagne’s surface area, followed by Pinot Meunier (32 percent) and Chardonnay (30 percent). Other approved varietals are Arbanne, Petit Meslier, Pinot blanc and Pinot Gris that together represent less than 0.3 percent of plantings.

After the grapes ripen - usually in autumn - around 100,000 pickers, porters, loaders and press operators descend on the vineyards of Champagne for the three-week harvest.

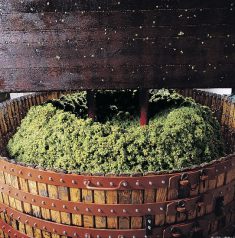

Once picked, the grapes must be pressed following the specifications of the Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC).

Each type of grape variety is pressed together and sorted depending on the ‘cru’ of origin. Juice extraction is strictly limited to 25.5 hectolitres per 4,000 kilograms. The first pressing (the cuvée) makes up 20.5 hectolitres, and the second pressing (the taille) produces 5 hectolitres. The traditional press is still widespread in Champagne, though some have switched to more modern machines, such as the pneumatic press.

As the juice is extracted, it flows into open tanks where it is treated with sulphites. These help to inhibit the growth of mold and unfriendly bacteria and their antioxidant action safeguards the physicochemical and sensory quality of wines.

As the juice is extracted, it flows into open tanks where it is treated with sulphites. These help to inhibit the growth of mold and unfriendly bacteria and their antioxidant action safeguards the physicochemical and sensory quality of wines.

After the sulphuring process, the musts are clarified by adding flocculant matter that captures other particles in the musts, which then forms sediment at the bottom of the tank. After 12 to 24 hours, the clarified musts are transferred to stainless steel or wood vats for fermentation.

Historically, winemakers relied on the presence of natural yeast on the grapes to trigger fermentation, but the results were unpredictable. Nowadays, to help start the fermentation process the producers add two products to the clarified musts. One is sugar and the other is yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), which consumes the sugar and excretes carbon dioxide and alcohol. The yeast also releases molecules that have a major effect on the wine's aromas and flavours. This process must be done at a temperature between 10 to 15 Celsius to avoid the yeast dying.

Once the fermentation is finished, the wine goes through malolactic fermentation, a bacterial reaction that converts malic acid to lactic acid. Prior to the 1960s, it is probable that it did not occur in most Champagnes as it only happens naturally when the required bacteria are present and when the ambient temperature rises high enough. The process was artificially introduced to mitigate Champagne’s high acidity and make young wines more drinkable. It provides a certain richness on the palate and smooths out acidity, sometimes resulting in creamy, buttery flavours.

The alcoholic fermentation process takes only a couple of weeks and once finished, the wine remains in a tank or barrel until it is time to blend.

Some producers blend as early as January following the harvest, but many producers wait until April or even later in order to age the lees. While most of the wines from any given harvest will be used in that year’s blend, those that have a greater potential to age well are put aside as reserve wines. These are used to create Champagnes of special complexity and quality and can also be stored and bottled later as a vintage Champagne.

Once the wines are blended, they may be cold stabilized and held at that temperature for twenty-four hours or more to precipitate tartare crystals, which prevents their formation in the bottles later. After the stabilisation, the blended wine may be filtered before being put into tanks for a short time to allow the various components to integrate before bottling.

Aging on lees

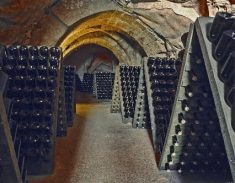

Aging on leesAfter fermentation, the lees remain in the bottle until disgorgement (the moment when the lees sediment is removed). Lees aging enriches the palate, giving the wine more breadth and depth, and creates the nutty notes typical of Champagne. Much of this is due to autolysis, the enzymatic process that takes place after the yeast cells die and break down. This process can continue for years.

To prepare the bottles for disgorging, all the sediment left from fermentation is coaxed into the neck of the bottle through a procedure called riddling. This is a labour-intensive process where bottles are held by the neck in A-frame riddling racks called pupitres. A remuer turns the bottles by hand and regularly tilts them downward at a small angle until the bottles are almost vertical so that all the sediment is collected in the neck

Bottles can be disgorged by hand by dipping the neck’s bottles into cold water, which partially freezes the sediment. When the cap is removed, this semi-frozen plug of spent yeast cells comes out with it, leaving the rest of the wine clear.

Immediately after disgorgement, the bottle is topped with a liqueur d’expédition, which is wine mixed with a little cane or beetroot sugar. This serves two functions; it replenishes the small quantity of wine lost through disgorgement and it introduces a precisely measured quantity of sweetness called dosage.

Dosage amounts are strictly regulated according to the style of Champagne winemakers want. For example:

Brut Nature, Non-Dosé, or Brut Zéro: bottled without any dosage and with no more than three grams of residual sugar remaining from fermentation.

Extra Brut: 0-6 grams of sugar per liter.

Brut: 0-12 grams of sugar per liter.

Extra Dry: 12-17 grams of sugar per liter.

Sec: 17-32 grams of sugar per liter.

Demi-Sec: 32-50 grams per liter.

Doux: more than 50 grams of sugar per liter.

Once the wine has been dosed, a cork is secured in place by a wire cage topped by a metal cap. Champagne corks used to be made out of a single piece of natural cork bark. Today, they are usually composite cork: the main body is made up of agglomerated cork, while the end that is in contact with the wine is from two or three disks of natural cork.

Blanc de Blancs: A Champagne made exclusively from white grapes, which almost always means that it is 100 percent Chardonnay.

Blanc de noirs: A Champagne made exclusively from red grapes. It can be either Pinot Noir or Pinot Meunier or a blend of the two varieties.

Rosé: Most often made by the blending of a little red wine with white wine.

Nonvintage: Blended from multiple vintages, a nonvintage brut is generally a producer’s entry-level Champagne. But many producers, especially grower estates, have an upper-level nonvintage wine made from a stricter selection. This can be a higher quality than basic nonvintage Champagne.

Vintage: Blended exclusively from the base wines of a single year, vintage Champagnes tend to be made from a high-quality selection of grapes and exclusively from the best harvests.

Prestige Cuvée: These wines represent the most meticulously selected, most expensive, and presumably the highest quality Champagnes in a house’s range.

Single-vineyard: A Champagne that is made entirely from a single parcel of vines. This can be nonvintage or vintage dated.

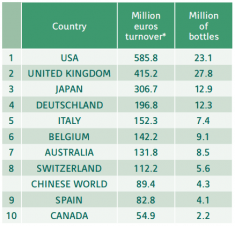

In 2017, the total turnover of Champagne reached a record value of 4,900 million Euros, mainly due to the growth in exports (2,800 million Euros, 6.6 percent more than in 2016). The French market remained stable at 2,100 million Euros. The United States remains the leading export market in value (586 million Euros), an increase of 8.5 percent compared to 2016. The United Kingdom is the next largest market though it continues to be negatively affected by the ‘Brexit’ effect, with sales falling by 5.7 percent and a markedly reduced volume (down by 11 percent).

Japan (the third largest export market) has seen strong growth in both value (21.3 percent) and volume (17.6 percent). The image is more heterogeneous in Germany where turnover has increased by 1.7 percent, but volume has decreased slightly (by 0.8 percent).

In Asia (which accounts for 15.5 percent in volume and 19.2 percent in value), the Chinese triangle (mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan) has seen particularly dynamic growth, with an increase of 26.7 percent in value. Exports to South Korea are also impressive (an increase of 39.5 percent in value), with sales exceeding the threshold of one million bottles.

After a slowdown in 2016, the African continent is rebounding (an increase of 7 percent in both volume and value).

Top 10 Export Markets in 2017

In Oceania, sales to Australia continue to grow (up 23 percent in value) despite a less than favorable exchange rate, while the New Zealand market is also on the rise (an increase of 12.9 percent in value).

Sources:

“Champagne: The Essential Guide to the Wines, Producers, and Terroirs of the iconic region.”

https://www.champagne.fr/assets/files/economie/filiere-champagne/plaquette_fili%C3%A8re_uk_2018.pdf