May 10th, two new Chinese independent productions showed at the Cinema CityClub of Pully: One Child by Mu Zijian and Laughing to Die by Zhang Tao. Both films represent the “new generation” of Chinese independent film production.

The event took place in association with the Chinese artist Mingjun Luo’s art exhibition Here and now that was on display at the Pully Art Museum until May 15th.

The event took place in association with the Chinese artist Mingjun Luo’s art exhibition Here and now that was on display at the Pully Art Museum until May 15th.

Following the showings, Gérald Béroud, creator of the internet-based Swiss-China exchange platform Sinoptic and president of the Section Romande de l’Association Chine-Suisse, led a discussion about Modern China. The lively exchange revolved, in a large part, around a China trapped between traditional culture and Western values, with prevalent themes of family and death.

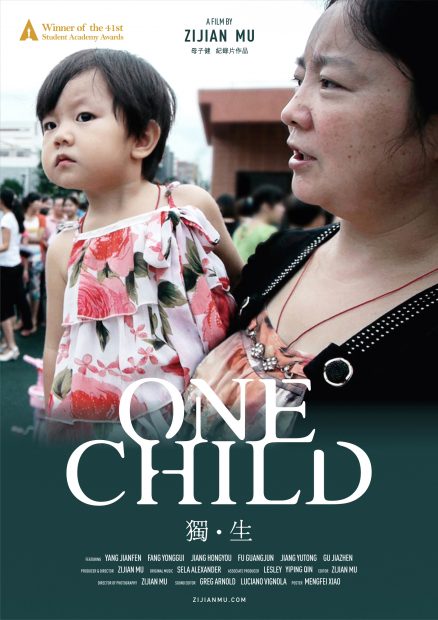

One Child

Produced in 2014, the documentary One Child shows the effects of the ‘One Child Policy’ in the context after earthquake of 2008 in Sichuan, a tragedy in which many children lost their lives.

The camera follows the destiny of three families who deal with loss. In one case, a woman wants to adopt a child but her husband refuses. The second family is lucky enough to get pregnant again, and a baby of the “reborn” generation is the result. In the third case, a widower turns to Buddhism.

Laughing to Die

The fiction Laughing to Die, also produced in 2014, is a story of a family in which the ageing mother becomes a “problem”. In rural China, the woman’s six children, grown adults, are trying to send her to a retirement home, but no room is available. They decide to take turns letting her live with each of them, and looking after her. However, they struggle with her health problems, the lack of money, and other issues. Frustration grows.

The Sinologist’s input

After showing both films, Gérald Béroud shared with the public certain aspects of Chinese culture regarding family. He used chengyu, Chinese proverbs in four characters, to explain. Below are some of the proverbs and how they related to the themes present in the films.

多子多福 / More boys means more happiness

Having a boy over a girl has always been a priority in Chinese culture. The main reason for this is that a boy is believed to be the bloodline, unlike girls who leave their family to join the in-laws.

This cultural aspect became even more crucial when the One Child Policy came into effect in 1979. The earthquake in Sichuan led to an exception to the policy, as parents who had lost their only child were allowed to have another.

不孝有三,无后为大 / “There are three ways to be unfilial; having no sons is the worst” (Mencius)

According to the Confucian heritage, a child should be filial, meaning children should be obedient and provide for their parents. In the film Laughing to Die, the children feel obliged to look after the mother. This, however, creates problems for them.

In the second part of Mencius’ proverb, the importance of having a boy is reiterated. As we see in the film One Child, adoption often becomes an option for poorer families who have two daughters, not two sons.

家国一体 / Family and State are one

Very patriarchal indeed, in Chinese culture, the State is often compared to the family. The word for country is actually 国家 – guójiā, the first character meaning state, the second meaning family.

In Chinese culture, unlike in the western world, happiness and prosperity is only possible in a large family with many children. This explains why, even with the One Child Policy, the population has continued to grow. Furthermore, for the Chinese, the positive development of a country is also dependent on a growing population.

The elderly and death

The elderly is also a theme that the story in Laughing to Die depicts very clearly. If in the West, there is some help for older people, China still has not introduced a system to aid the ageing population. Families are often still responsible for caring for the elderly. However, Gérald Béroud shared with us how in some regions, such as in Jiangsu province, a fairly rich province, things are changing. On one of his trips, he had the opportunity to visit retirement homes. He also confirmed that the question of the growing elderly population is indeed in the State’s line of focus.

Death is another reoccurring theme in the films shown. In the documentary One Child, during a traditional celebration, the day of the Phantoms, a woman and her sister cook the traditional nine dishes to share with the loved ones in death. In Laughing to Die, the last scene is the old mother’s funeral. All dressed in white (the color of mourning in China), the family celebrates by organizing an obscene dance show, not appropriate for the occasion but meant to attract people to the funeral.

When talking of death, we imagine the death of people. However, in the documentary One Child, the death also represents that of a city, Beichuan. After the earthquake, locals mourned their lost loved ones and saw their homes destroyed. Many had to move into new, soulless flats, built fast to relocate the population. It was a “death” in many senses for a lot of people.

A cultural event such as this one is the opportunity for the general public to discover aspects of Chinese culture that we in the Western world do not often encounter. It was clear that having an expert such as Gérald Béroud helped the audience to better understand the context and cultural nuances depicted in the films. The variety of topics linked to the two short films is rich and complex. Watching them helped the viewers gain a glimpse of what China is going through as it continues to mix tradition and modernity.

Sources:

https://zijianmu.com/

https://glosbe.com/zh/en/%E4%B8%8D%E5%AD%9D%E6%9C%89%E4%B8%89,%E7%84%A1%E5%BE%8C%E7%82%BA%E5%A4%A7

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/nov/02/chinas-great-gender-crisis

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/funeral-strippers-beijing-cracks-down-on-uncivilised-practice-of-using-exotic-dancers-to-attract-10199606.html