MOOCs hit the headlines in 2008. They became a craze by 2012, and by 2015, the phenomenon had peaked. The MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) that eres going to transform education, and especially higher education, by making it free and available to anyone anywhere, had stumbled. As an emergent technology, this is not unexpected.

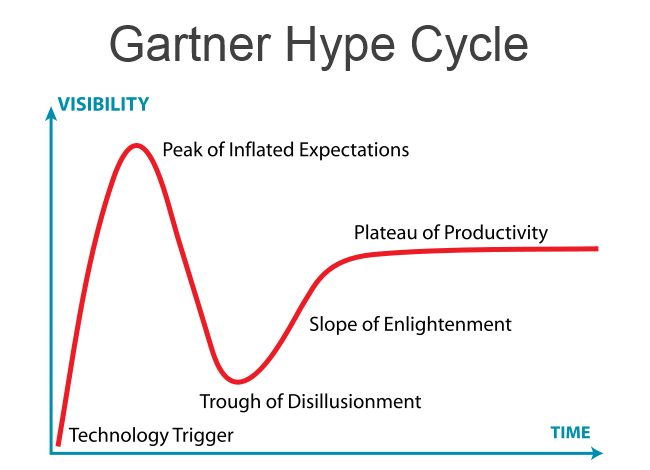

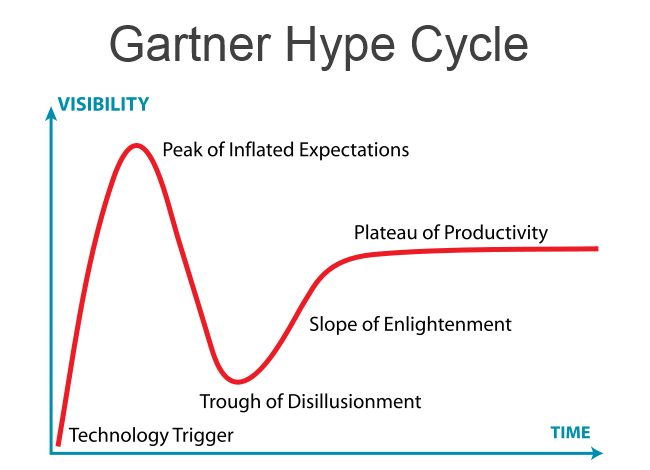

The Gartner Hype Cycle graph captures the lifecycle of new or emergent technologies. If we follow this logic, the MOOC, or more generally, Technology and Education, is now probably through the Trough of Disillusionment and making its way up the Slope of Enlightenment. Are MOOCs the endgame on the Plateau of Productivity, or just another milestone in the journey to transform education through technology?

The Gartner Hype Cycle graph captures the lifecycle of new or emergent technologies. If we follow this logic, the MOOC, or more generally, Technology and Education, is now probably through the Trough of Disillusionment and making its way up the Slope of Enlightenment. Are MOOCs the endgame on the Plateau of Productivity, or just another milestone in the journey to transform education through technology?

The stumbling block has been the MO – Massive and Open –and what this means for education. The OC –Online and Courses –is less of an issue, as these have been around for a relatively long time. Online, as in a connected state, and courses started with correspondence schools and evolved into the online distance learning championed in 1969 by the UK Open University. This model of distance learning was endorsed when top universities such as MIT and Stanford started providing online courses. But it was the MO properties of free, open and tens of thousands of participants that really lit up the imagination and the possibilities to transform education.

The Massiveness, and to some extent the Openness, was enabled by the scalability that technology brings. It solved access and distribution. However, that raised other issues. Large numbers of people started a course but very few finished the course –less than 10%. This is still a large number of people (given the numbers who start), but this completion rate is extraordinarily small compared to the traditional classroom course. Udacity is the example of this. It was one of the first MOOC companies with a mission to democratize and transform education, but it wheeled after a couple years because of the extremely low completion rates. To a paid, corporate training model, basically free, huge and online doesn’t transform education if very few pass the course. A discussion on a business model for MOOCs almost concedes the ideological high ground for openness. If a course requires a fee, then it’s not open. Using the MOOC as a form of advertising so that more people sign-up to a fee paying course also compromises the goal of openness.

What does this mean for MOOCs in general and its two primary forms; the cMOOC and the xMOOC? cMOOCs are less affected because of their connectivist approach to education, which is enabled by participants using social media, content sharing, redistribution, and little to no formal assessment. Massive and Open, the scalability that technology brings to education is a basic objective of the cMOOC.

The xMOOC is more conflicted, because it is based on the traditional classroom model with a fee-liable curated content, a relatively classic teacher-student relationship, and formal assessment. The concepts of being Massive and Open in the xMOOC have struggled against an institution's need for a business model and the MOOC participants’ demand for formal certification.

The fervor that initially surrounded MOOCs in general, or more specifically the impact of technology on education, has faded. However, the MOOC has promoted the acceptance of online learning, and enabled change and diversification in the way that education in the classroom and online is delivered.

Some ways in which it has done so are:

- The flipped classroom – the formal content is presented online, and the classroom is used for Q&A.

- Playback – students can replay online the course materials, presentations and discussions.

- Timetable – Course participation is not tied to a strict daily or semester timetable or to a physical location.

- Duration – Online courses are shorter and more intense.

- Certification – new types of awards and certifications are available for online courses, and can count as a credit towards a conventional qualification.

Online teaching and learning is now part of the future of all universities. MOOCs should be seen as a project for the offering of regular credit programmes online at scale.2 However, it is unlikely that MOOCs will replace the traditional classroom in the near future.

Images:

Jeremyah, via Shutterstock

Gartner Hype Cycle Graph - Jeremykemp at English Wikipedia , via Wikimedia Commons

Sources:

https://mccglc.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/2000px-gartner_hype_cycle.png

2 Massive Open Online Courses: what will be their legacy? John Daniel

http://femsle.oxfordjournals.org/content/363/8/fnw055#sec-15

The Gartner Hype Cycle graph captures the lifecycle of new or emergent technologies. If we follow this logic, the MOOC, or more generally, Technology and Education, is now probably through the Trough of Disillusionment and making its way up the Slope of Enlightenment. Are MOOCs the endgame on the Plateau of Productivity, or just another milestone in the journey to transform education through technology?

The Gartner Hype Cycle graph captures the lifecycle of new or emergent technologies. If we follow this logic, the MOOC, or more generally, Technology and Education, is now probably through the Trough of Disillusionment and making its way up the Slope of Enlightenment. Are MOOCs the endgame on the Plateau of Productivity, or just another milestone in the journey to transform education through technology?

As a new term to me, and having read this very interesting article, I have one question, who pays for the production, server space and materials?

If an organisation, person or any group has an idea for a MOOC and wants to produce and get it out there on the web then there are basically three ways to fund the cost of this (which includes, production, server and materials costs):

- Themselves - out of their own pocket. So they pay for; research, content, production, server, hosting, maintenance etc...

- MOOC hosting platforms. Examples would be Udacity, Coursera, EDx... these can pay the full costs of the MOOC or some part of the costs

- Third parties - something similar to angel funding or maybe just benevolent or charitable funding

MOOC funding is a key question especially as the business model for MOOC's in higher education is not yet fully established.