Musée d'ethnographie de Genève (MEG)

Towards new nature-cultures

The distance we establish with our surroundings shapes the backdrop onto which we project an idea of self.

Within the western-world, selfhood has often meant an ever-increasing detachment from such a backdrop.

One of the most obvious outcomes? The separation of Men from Nature. A divide that, far from being merely psychological, has played an operative part in framing what can be extracted and exploited, which resources and whose work and lives matter, and which do not. As a political tool, it has been of paramount importance: without first accepting and naturalizing this hierarchical division it would be harder to accept unbalanced relations of power, kinship and wealth.

In trying to face some of these genealogies, the Musée d’ethnographie de Genève (MEG) has recently unveiled plans for a complete overhaul of its curatorial strategy, which includes changing its own name.

The central goal is to challenge the colonial facets at play – including the term ethnology itself – and, following the footsteps of similar cultural institutions throughout Europe, address the troublesome histories of how the museum’s collection was assembled.

As underlined by the MEG’s director Boris Wastiau, the main purpose is to put in practice a “decolonial process” that recognizes “relations which brutalized, deprived of power, made anonymous so many people and obscured so many practices and events in history”.

A question of restitution

An important part of this process is the restitution of some of the collection's objects.

Still, restitution is not the be-all and end-all in this exercise of making present to ourselves the meaning of our collective actions.

The MEG permanent exhibition "Les Archives de la diversité humaine"

Museums are invaluable spaces of narrative creation and continue to be crucial in the propagation of mainstream macro-histories that normalize and contribute to the disenfranchisement of cultures all over the world.

Communities of sound

Amidst the current capitalocene - with a raging climate crisis, viral pandemics, toxic patriarchy, and unabashed racism - we are somewhat reawakening the spirit of the globalized awareness of the 1960s and 1970s counterculture.

To support this urge in shaping new common grounds, assistance can partially come from a tool that was also crucial during those decades. Coincidentally, this tool is a type of art seldom featured in contemporary and modern art museums but which plays a central part in anthropological and ethnographic studies and institutions: music.

The connection between music and political intention is umbilical. As Geneva’s prodigal son Jean Jacques Rousseau recalls in his essay On the Origin of Language, the emergence of political life necessarily leads us to music. In his words, speaking and singing were "formerly one". They formed a unique body of music-speech that, as such, constituted the first social institution and translated some sort of "morality" or political will.

Since Rousseau, the connection between music and political intent got increasingly fragmented. Today, even politicized sub-groups of underground culture are, with growing nimbleness, quickly transformed into commodities. And lest we forget elevator music.

Still, it is important to see music as a language, to receive it not only as sound, notation, or escapist product but to try to understand its underlying social principles. Even anodyne elevator music has a function: it is recurrently deployed as a tool to regulate and manipulate consumer behaviors and workers' productivity.

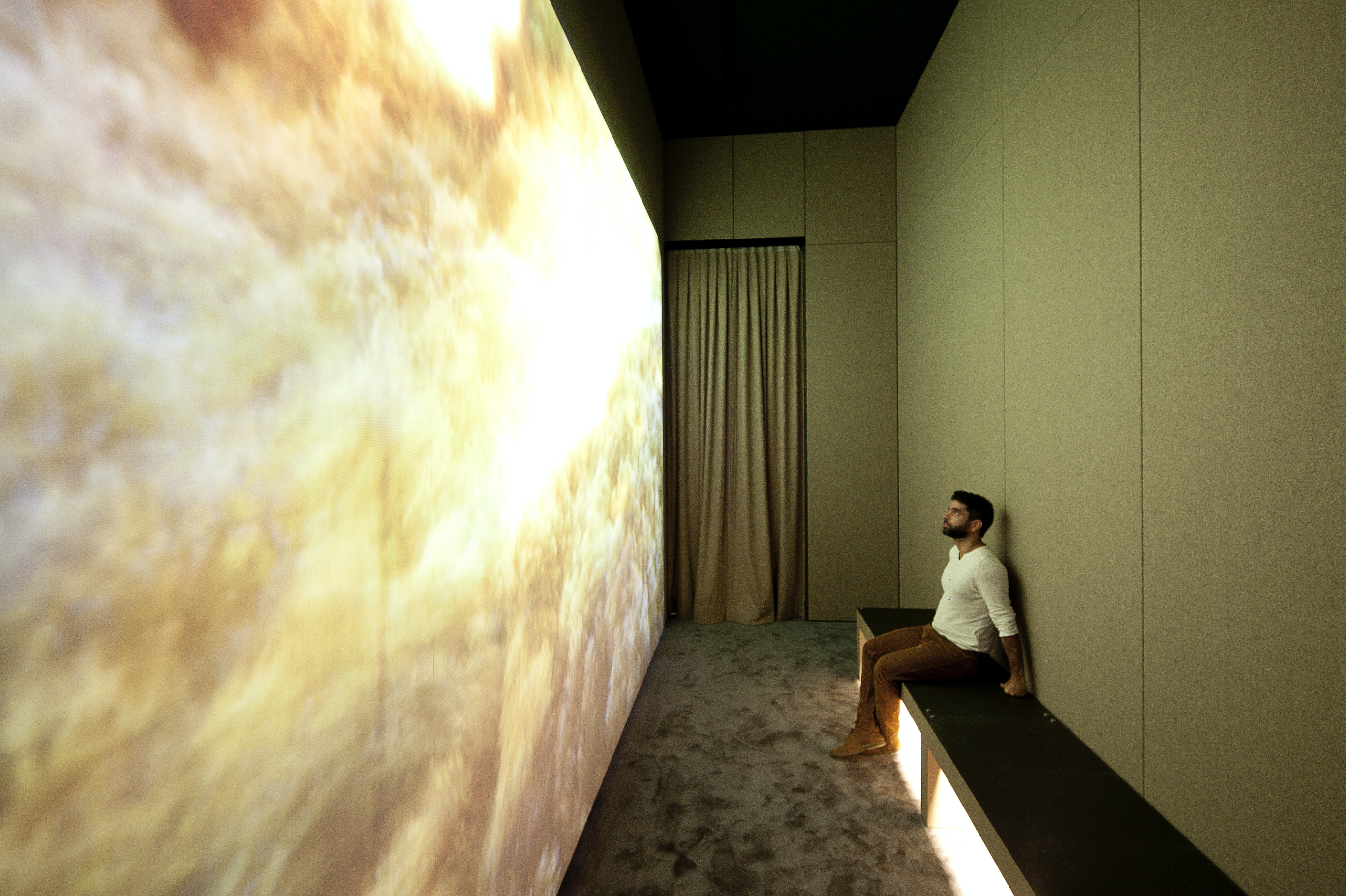

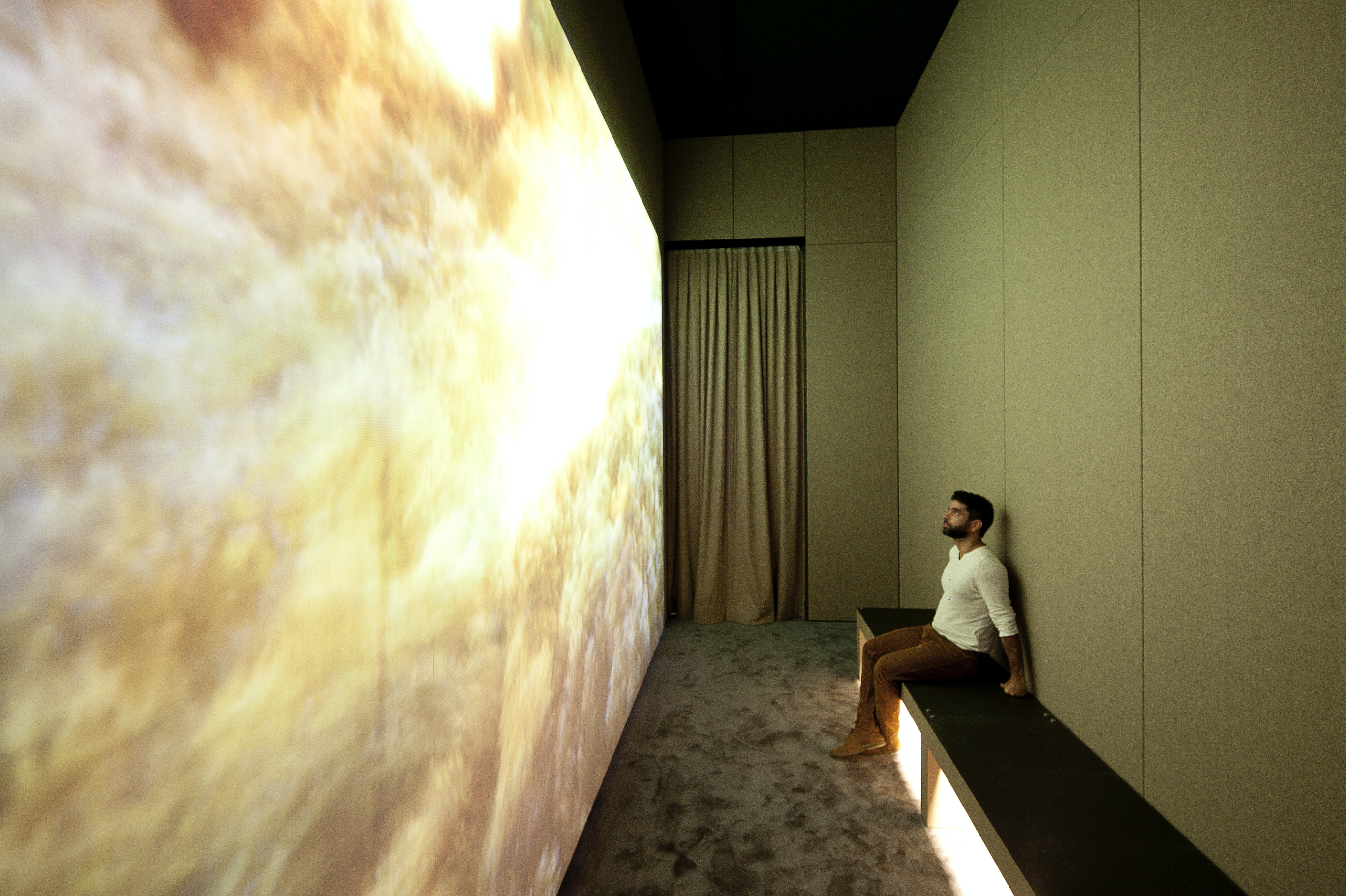

"Chambre sonore," an audiovisual installation that is part of the permanent collection.

MEG: Crossing music's borders

Within such a scenario, ethnographic and anthropological museums can be key in reawakening the political nature of the old unitarian music-speech because they have always dealt closely with artificial categories of separation. One such category is the dwindling but still pervading concept of world music, an umbrella term used to designate all non-Anglo-Western music. As composer David Byrne underlined in a visceral op-ed published in the New York Times, this is a designation that “ghettoizes most of the world’s music” and, at the same time, propagates “the myths and clichés of national and cultural traits”. In this context, world is to music what nature is to man. World: a prêt-a-exploiter repository of otherness painted with a fresh coat of authenticity.

Despite all this, music continues to hold within itself an outstanding potential for revolutionary and participatory action. Not only as the inspiring memory of collective ways of thinking but through its sheer capacity to foster temporary autonomous zones where usual protocols of behavior are suspended and pre-conceived mental dispositions are readdressed. Institutions like the MEG will always face the temptation to delimit an authentic, uncontaminated, original other, but they can also help tread a path towards a more referential understanding of cultures by creating allusions that encourage empathic thinking. By going beyond objects whose weirdness might obscure their original meaning, they can have a role in creating feelings of belonging and empowerment instead of being simple cabinets of curiosities.

It is possible to find within difference the elements that bind us together. The effort here is to tackle the polarity between center and periphery and reconnect the network of power relations back to our own lives, tribulations, and privileges. Not only to resolve feelings of guilt but to act on it. To accept differences not simply as exotic but as an opportunity to discover ourselves. As David Byrne put it, to cross "music's borders in search of identity".

Unveiling common grounds

When it comes to music in particular one should note that the MEG has a relevant history that dates back to the work of the ethnomusicologist Constantin Brăiloiu. During the 1940s and 1950s, he was responsible for the establishment of the Archives Internationales de Musique Populaire (AIMP) and the edition of the first-ever anthology of worldwide traditional music.

From the 1980s onwards, due to the effort of former MEG curator Laurent Aubert, the archive received more attention and was central to many of the music department's editions. Throughout the last decade, under the guidance of Madeleine Leclair - current curator of the MEG music department and responsible for the AIMP - the sound archive has once again experienced a renewed impetus. One important development was the establishment, in 2019, of a new collection that aims to present the archives through thematic selections that go beyond geographical and national delimitations.

The first outcome was the publication, in partnership with Mental Groove Records, of Soothing Songs for Babies, a compilation of lullabies from all over the world. A simple exercise which, by focusing on a kind of song present in almost all cultures, allows for feelings of otherness to dissolve behind disarmingly fragile and fleeting interaction, such as that of adults singing their children to sleep. Another ongoing project, organized in collaboration with the WAV33 platform and entitled Le Revéil des Archives Sonores, also tries to further create bridges with the public at large by inviting local deejays to compose sets that mix the MEG's archives with the goal of promoting unforeseen musical encounters.

Geneva-based deejay Androo performing live during the "Le Réveil des Archives Sonores program"

Actions such as these are interesting steps to search for new modes of reappropriation and imagination. To problematize communication from the mutualist point of view of co-shared living. They hint at the possibilities that arise if we re-orient our western-self from the uncommon towards the common, from simple observation towards the committed construction of a translocal political community. A community in which, through the entangled acceptance of what is foreign to us - including what philosopher Édouard Glissant called the right to opacity - we might discover how to embrace "every passion of the world, of the living, of the tremor by which being is provoked" that "begins with this consensual lack: the One.".

Notes:

This rebranding effort started to be more evident from the 1990’s onwards and has since led to a number of name changes in local museums, (not just MEG) such as Basel (1996), Berlin (2001), Gothenburg (2004), Vienna (2013) and Munich (2014).

Boris Wastiau et al., 2020-2024 Strategic Plan (Geneva: City of Geneva, 2019), 14.

The MEG has occasionally addressed the issue, like in the mediatic 2011 repatriation to Chile of the four Chinchorro mummies, which the museum helped supervise.

Jean Jacques Rousseau, On the Origin of Language (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986), 51.

David Byrne, I hate world music, The New York Times, October 3, 1999.

Édouard Glissant, Poetic Intention (New York: Nightboat Books, 1997), 7.

Further Reading:

Archipelago – Architectures for the Multiverse by Tiago Trigo